Unimportant Musings

Where an amateur attempts at divining somewhat passable insights.

Currently reading

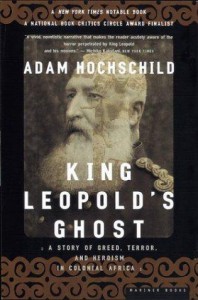

Book Review: King Leopold's Ghost

Scrolling through my past reads, almost all of them fiction, it struck me how much my reading could benefit from more variety. The first non-fiction book I bought, as far back as I can remember, had to do with futurism, and I never did finish it. Scandalous! What non-fiction I've dabbled in since then has tended to be predictable and safe: Bill Bryson books monopolize the part of my bookshelf that I, perhaps too idealistically, reserve for non-fiction. My non-fiction inexperience notwithstanding, Bryson's A Short History of Nearly Everything has been comfortably holding onto its Most Amazing Non-Fiction Book I Ever Did Lay Eyes Upon title without any real danger of losing it. That is, until I read King Leopold's Ghost.

I knew beforehand the book promised to be a worthwhile investment. It's a familiar sight wherever requests for non-fiction book recommendations pop up. Initially, there was skepticism on my part; it is easy to be overexcited. But the big surprise driving my thoughts as I was finishing up Ghost, apart from the slight betrayal of the last 60 pages comprising the author's notes, bibliography, and index, was how much people have undersold its quality. Adam Hochschild has done for history what Bryson has done for science: he made it exciting. That's about where the similarities end. Laughs were had while reading Bryson. With Ghost, however, there was just the silence of horrified surprise. Hochschild had the arguably easier job than Bryson's, whose ambitious task was to tackle much of high-school science and not bore us in the process, when the former's was only to focus on one part of history, yet his account is no less comprehensive or compelling for it.

Because of the abundance of summaries for the book here as elsewhere, I'll not waste any time in writing another one, but suffice it to say that around the turn of the last century, a king too clever and power-hungry for everyone's own good homed in on the Congo, which he in his rush for profits was quick to squeeze dry, along with ten million lives (as many guesses put it; records were either poorly kept or incinerated), from afar while most of the world watched on. "Leopold" doesn't immediately jump to mind when you think of history's most odious villains, flooded as you are with images of death camps and gulags, and such ignorance is largely thanks to the man's PR machine still operating even after his death. Access to what official records that survived the fire was impossible, and not that much less so even for Belgian ambassador Jules Marchal: "There was a rule in the Foreign Ministry archives. They were not permitted to show researchers material that was bad for the reputation of Belgium. But everything about this period was bad for the reputation of Belgium! So they showed nothing."

Through extraordinary organizational skills and political sleights of hand, Leopold had the world fooled. No country that mattered didn't have at least an agent of his waiting for instructions to woo their respective country. "[T]he king reached new heights as a illusionist. He or one of his stagehands managed to open the curtains on a completely different set each time, depending on the audience." For the Americans, Leopold's American agent justified the International African Association, one of Leopold's several front organizations created for supposedly humanitarian reasons, by describing it along the lines of Travelers Aid and appealing to their anti-slavery sentiments; for the British, the organization was painted as "a sort of 'Society of the Red Cross'" that would advance "the cause of progress;" and for "the more military-minded Germans," Leopold compared "his men in the Congo to the knights of the Crusades." Ghost is really most enjoyable when Hochschild, with his straightforward writing and knack for presenting history almost cinematically, delves into Leopold's political machinations.

In Ghost's first half, named "Walking into Fire," is mostly world-building, all of it fascinating. Hochschild starts with Leopold's childhood, but doesn't linger overlong on anything before moving on to the next necessary bit to set the stage, the story's as well as Leopold's, of which infamous explorer Henry Stanley Morton is the main event. Next come a lot of exploring, deception, political maneuvering, land thievery, and regime establishment, followed by the rubber terror of the chicotte, decapitated heads, and chopped-off hands, and Hochschild chronicles all this with fantastically readable writing that, because of its strong narrative and stranger-than-fiction content, made me question reality at times. Watching Leopold getting his way every time can be exasperating, and probably because of that, there was a point around page 140 where, for the longest time, I didn't pick the book back up and continued where I left off. My brain, either being helpful or having fun at my expense, decided that spring cleaning was in order, leaving me at a total loss when I finally got back into Ghost months afterwards, which sent me back to the first page. While knowing that the pacing really picks up 37 pages later, just before Ghost's second half, would've been helpful, re-reading most of the first half was, if possible, even more absorbing than my initial run-through. I caught up in no time at all.

Just before the second half begins, we are re-introduced to Edmund Morel, Leopold's loudest opponent yet, who we meet in the book's first few pages as well as in its blurb, and from here, Ghost practically reads itself. Titled "A King at Bay," the second half is the long-awaited payoff of suffering through Leopold's victory after another in the first. Hochschild peoples the rest of the chapters with colorful characters of inspiring courage, breathtaking intrigue, and comical misfortune. Whereas "Walking into Fire" sees Leopold masterminding events, "A King at Bay" finds them unraveling. Hochschild's stellar writing and confident narration here, once again, seldom falter, and it increasingly bummed me out the closer the end seemed. After getting over my irritation at the book ending with 60 pages left to go, I took some time to gather my thoughts. Then I took still more time. Almost a month later, I'm typing up this review, all to say that, despite the reader's block putting a snag in things halfway through, I loved Ghost. Well-written, lucid, and thoroughly supported, Hochschild's exposé should have King Leopold's Ghost quaking in his spectral boots.

1

1

2

2