Unimportant Musings

Where an amateur attempts at divining somewhat passable insights.

Currently reading

2

2

Review: Team of Rivals

Abraham Lincoln had always seemed to me, an outsider flattening my nose against the fishbowl of American history, generally a big deal. In his story's oversimplified version, he kept his country together, freed slaves, and was all but deified upon his assassination. The man was, even if everyone else at the time didn't know it, "still too near to his greatness" as they were, "[h]is genius... still too strong and too powerful for the common understanding, just as the sun is too hot when its light beams directly on us," as Leo Tolstoy put it, a veritable badass. Pitting him against vampires was redundant. The broad strokes of his life were already very well-known to me, burned into the public consciousness as they have been by more books, biopics, and occasional pop-culture references combined than any one person save Doris Kearns Goodwin with her superpowers of research and organization can know what to do with. Most people are usually content enough not to investigate any further.

Review: Crime and Punishment

Did Fyodor Dostoevsky know what fame and glory, to raise his status even more long after his death, awaited him when he began writing? My curiosity extends also to other authors in the same ballpark. Even if he had only an inkling, that still had to have provoked from him no small amount of dread. Very little can be said about Crime and Punishment that hasn't already been better said. Opinions have been exhausted, their points repeated, whole books written, feathers ruffled, epiphanies begotten, minds changed, and school assignments given. It's enough to give anyone mental constipation. But you can only stare blankly at your blinking text cursor for so long before you're waking up in the morning and thinking it's a good idea to go around axing faces and sundries, so here's the rub: C&P is 11-star material. Anything else to that singular thought, which has launched yet more of the same but frenzied and wordier, is extraneous. The first sentence, in which our shifty-eyed antihero leaves his apartment building in a state of "[indecision]" towards some unnamed bridge, aroused my curiosity; the crime, Dostoevsky's description of which is as engaging and breathtaking as it is horrifying and even comical, secured my attention. If Dostoevsky were an airline pilot, don't expect the seat belt sign to go off anytime soon.

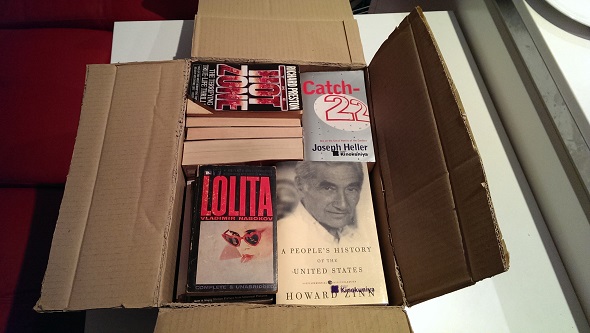

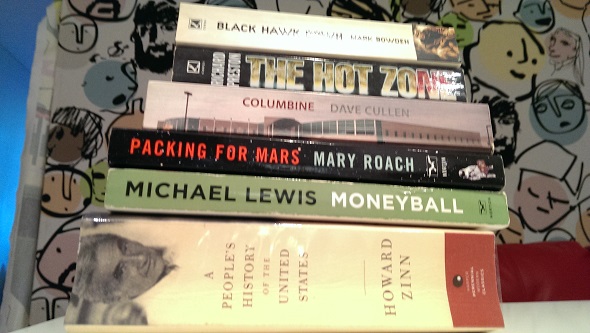

Some of my books arrived from overseas a few days ago. Thanks, Mom!

How have we not invented teleportation yet? Then I could've had my entire library beamed here without having to cut off my arm and leg for it in shipping fees.

Anyway, this reunion has me all verklempt.

Review: Dead Souls

We can thank our lucky stars for writer's block, as we'd likely have set fire to the Dead Souls manuscript ourselves if Nikolai Gogol hadn't. Had he, overcome with religious fervor, forged ahead with his plan and complete this three-parter, separated into volumes each of crime, punishment, and redemption, and not starve himself to death, we might've had on our hands a literary misfire it seemed like he, previously so promising, wanted to unleash upon us expectant and unsuspecting masses. Fortunate is everyone, then, that the first (and undeniably best) volume, where Dead Souls plays out its main story, can be taken as more or less self-contained. The second one, while still dazzling in places with great writing, sparkles less so than its predecessor not only because of disjointed chapters, missing words, and lost pages, but also because hints of a crazier and preachier Gogol, already exasperating his friends and fans in real life, start to emerge then in the text. In his later years, he had at one point consoled a critic who had recently lost his wife by this bit of classiness: "Jesus Christ will help you to become a gentleman, which you are neither by education or inclination—she is speaking through me." Another instance: Gogol advised in letters to his readers that "[t]he peasant must not even know that there exist other books besides the Bible." Village priests, he recommended, should accompany them everywhere, and even be made their estate managers. Lovely! It's all a little odd and, considering the incense-smoky shrine to him I'd constructed in my mind after his short stories had so brain-tinglingly won me over, thoroughly disappointing. For all that, on the bright side, what Gogol lit on fire was at least none of the first volume, leading even Vladimir Nabokov to conclude, in his chapter of Lectures on Russian Literature on the author, that "[Gogol] was destroying the labor of long years" not to cleanse himself of the sins he thought his books were, but "because he finally realized that the completed book was untrue to his genius." After that, it's hard to be mad at the guy.

6

6

Review: The Collected Tales of Nikolai Gogol

Nikolai Gogol, based on the image results my Google search spat back, reminds me of that quietly excited classmate who's usually game to tag along with you for some mischief-making. Whoopee cushions and joy buzzers presumably hadn't been around then, so one shudders at the tricks his imagination must've improvised. From his eyes shines a look too knowing not to have exposed his hastily-planned cover-ups and landed him in a few or hundred detentions, spent here sweeping grounds and there copying lines. In short: my kinda guy. Russian literature, since books began making me feel things, has been for me that scary mountain whose lack of obvious footholds has sent me running home into the squishier bosoms of easier genres, whose peak is peopled with happy campers roasting marshmallows while animatedly discussing scenes from this Dostoevsky classic or that Tolstoy epic. What sure hand would, as soon as I attempt the climb, save me from tripping over the first loose rock and snap my neck? Gogol's, while mindful to point out where not to step, wouldn't hold mine, yet what convinced me more to turn to his works first of all was learning of the ripples they caused that soon impacted on others' in waves. "We all came out of Gogol's 'Overcoat'," some dude said, which, prisoner to that tedious no-stones-left-unturned school of thought that I am, rather finally shut the case.

3

3

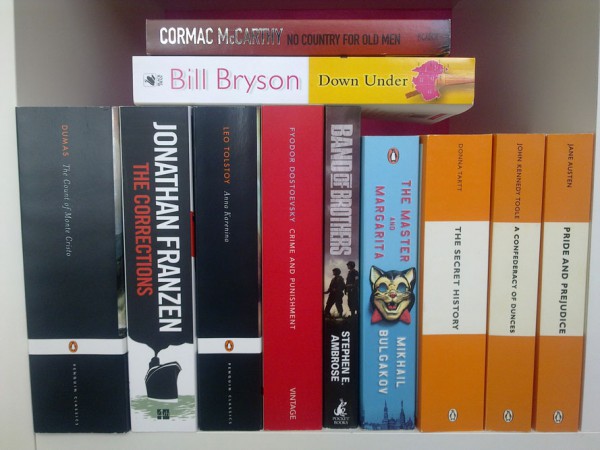

Review: The Count of Monte Cristo

The Count of Monte Cristo, at 1,276 pages, can read like it has either a quarter or quadruple that many. If context doesn't matter, a glance at how long it took me to swallow this Book¹, a statistic this site so helpfully provides, might lead one to the conclusion that I breathed an explosive sigh of relief when the end came—because, to clear the confusion, recording paint dry and watching the video at one-thousandth of the regular speed would've been more exciting and memorable than reading Count. The numbers don't lie: the journey began on January 1—you can almost feel the naive optimism in that choice of date—and ended on August 2, nearly exactly eight months later. How can anyone, after all, have nice things to say about that which took them that long to complete? The length of time taken to read a book, granted, doesn't necessarily indicate one way or another how well one got on with it. Those whose habit it is to make snap judgments, however, seem determined to pounce on that kind of quick and easy information wherever it appears.

2

2

Review: The Catcher in the Rye

There are three things you don't talk about on first dates: religion, politics, and The Catcher in the Rye. A casual survey over the tubes to gauge the general opinion on the book is guaranteed to fail. To Kill A Mockingbird, while we're on the topic of mandatory high-school reads, seems to be forever basking in the love the world holds tirelessly for it, occasionally poked at by random moral boners, and entirely unbothered by the obligatory contrarians. Catcher, on the other hand, enjoys nothing nearly so universal. People either adore or abhor it. Further complicating matters is the variety in the reasons they give for their love or hatred for the book. Catcher, not looking to budge a bit any time soon from its much-coveted spot among other literary giants, deserves its place in history because, as those justifications from the former camp typically go, 1) the main character just speaks to them, 2) the book captures a perfect snapshot of the fears faced by teenagers about to become adults, and 3) there's more to it¹ than meets the eye. From the other side, you encounter such retorts as 1) nothing happens in the book, 2) the main character's woe-be-me whining and hypocrisy, let alone his dark-sided atheist propaganda, drive even your most God-fearing Christians to suicide, and 3) J.D. Salinger duped us! That Catcher is polarizing as all get-out is hard to bring up without Nicolas Cage's disembodied head materializing now and here with his you-don't-say face. Indifference is impossible. It gets under your skin one way or another.

Review: The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay

Comic books are all the rage now, didn’t you hear? Look at what Marvel Studios, backed by Disney, is doing: building from the ground up and expanding an entire cinematic universe spanning across different franchises. Warner Bros., dollar signs in their eyes after seeing how much bank The Avengers made, and keenly feeling the emptiness in their vaults the Harry Potter series once filled so readily, scrambles to bring to the big screen their DC universe, stuffing Batman, with possible cameos from Wonder Woman, The Flash, and maybe even Nightwing (of all people), in a Superman sequel, which should end well. Sony, to tighten their grip on Spider-Man’s movie rights, looks to have villain spin-offs in the works. Then there’s 20th Century Fox, who’s realized you have to spend money to make money, and the resultant X-Men: Days of Future Past, uniting the old cast of the original trilogy with the new one of X-Men: First Class, is reported to be their most expensive production since Avatar. No longer the shameful secret high-school outcasts ferret away in their pockets every time the popular kids saunter by, superheroes have gone mainstream. It took a while, and it wouldn’t have been possible if not for a few dudes in the 30’s who started it all. Much goes on in The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, but at its core, the book is Michael Chabon’s love letter to comic books.

At the Movies: Catching Fire

Well, I'll be damned.

The second Hunger Games movie surprised me. That change of director made all the difference¹. That seizure-inducing shaky cam is gone, and good riddance, and almost everyone and everything was on point. What Finnick lacked in looks was more than compensated for by his characterization and acting, and Joanna just plain rocked, to say nothing of the old faces of Effie, Haymitch, Flickerman, and Snow, all of whom really stepped up their game this time. The movie, with a two-plus-hour running time, also had fantastic pacing; the pre-game hubbub was just as entertaining as the actual games. There were a few hiccups, but nothing deal-breaking. I got my money's worth.

But there's a hole in my memory where that abortion of a third book should be, so I pray they do their own thing and not let themselves be held back by mediocrity to rehash still more mediocrity. The world has enough to deal with. Actually, with the amount of angry skimming I did, I'd fail spectacularly at those cheesy quizzes concerning what went on in that book. Don't dare let Sutherland, Hoffman, and now Moore go to waste. If only Ender's Game, from what I've been hearing, which isn't making me brim with confidence, were half as good, but we can't have all the nice things.

¹Can Francis Lawrence go back and remake the first one?

A Series of Fortunate Events

I lucked out. A part-time job 15 minutes' walk from my place and working alongside awesome and laid-back people is already a godsend, but that it's at a bookstore sounds almost impossibly perfect. It probably is, so there go the chances for my inevitable biopic to become a box-office smash and critical darling because, aside from its low-budget production values and the main character's unrealistically good looks, the writing would seem much too far-fetched. Before I'm sent to an early grave by the overexcitement being surrounded by books so often will doubtless cause, I just want to say I love you all and not to worry because I go to my end with my funk on.

Progress: The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay (4%)

For some reason, I've so far kept the likes of Franzen and Chabon, Foer and Smith, Wallace and Pynchon at an arm's length (more like a very long stick's length in the latter's case). But this afternoon, at one of the many bookstores in the Sydney city, where I was killing time before my job interview among the shelves of books at prices so marked down as to cause changes of pants and empty wallets, I picked up Telegraph Avenue at random and skimmed through it. That's when I knew I could no longer put off Chabon. Then, after rushing home, on a high from the more-or-less successful interview (my trial run starts Monday!), I fired up my Kindle and selected The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, which if it were a person could probably relate to Bryan Cranston here:

On second thought, I ought to have started off with Chabon's worst books and then worked my way up, the same of which goes for Stephen King where I dove into It instead of, like, Cujo. The point is moot, anyway, as the only way anyone can make me drop this book now for another is if they pry my Kindle from my still-warm, lifeless hands. I had to stop reading for a moment at one point to be awed by the way Chabon described one of the main characters's eyes as being "wide-set blue eyes half a candle too animated by sarcasm to pass for dreamy," or by when he spoke of a character practicing a magic trick with "a masturbatory intensity of concentration." The imagination! If the rest of The Amazing Adventures is even half as fun as the preceding pages have been, I'm of a mind to, after securing my head inside a fish bowl with saran wrap, strap myself on to a rocket, go to space, bag myself five of the nearest and twinkliest stars, and mail them to wherever Chabon would then be, the kinks of which obviously need further consideration, without also hastening the man's death by exposing him to radiation, crushing him to death, or some such bad things stars do to us.

Review: Flowers for Algernon

Before seagulls with roiders' arms, Dolly, and Jeff Goldblum arguing about dinosaurs, there was Flowers for Algernon to ask the question: has science gone too far? After Algernon the mouse not only reached the cheese in variously arranged mazes faster than the other mice, but hasn’t for some time seemed about to spontaneously combust or collapse into a black hole, the go-ahead is given for Charlie Gordon, his I.Q. at 60, to undergo surgery to maximize his intelligence. From page one, Daniel Keyes drops us into Charlie’s head, through which we see the world via Charlie’s progress reports recording his day-to-day events and thoughts. It would be nice if, from the outset, Charlie had lived with a loving family. It would be nice if he brought home sweet-smelling bread and cakes he made with best friends who were also his co-workers. It would be nice if, at school, he met with someone pretty he could fall in love with. It would be nice if they all loved him just the way he was, of an intelligence society has agreed to be unworthy of further than a moment’s thought, and they all joined hands together and skipped merrily into the orange-golden sunset towards a happily-ever-after ending. It would be nice. But it would be wishful thinking, realized in some other book written in some other reality that probably no one would read because its niceness clashed with their expectations for plausibility, which Keyes is only too happy to accommodate.

Reblog: Getting to Know BookLikes

Links to various Booklikes tutorials around the site. Thanks to all the hardworking BL members and team who contributed. This is a work in progress. More links will be added as I find them.

14

14

1

1